|

The terrible disaster in Japan this month has left the world shocked (how could it be so brutal!), scared (what if it happens to us?) and confused (how dangerous is nuclear power?). The media is a fickle mistress, and the news is now dominated by Libya, Wikileaks and so on. But the scale of the earthquake, and the force of the tsunami after that has left everyone gasping for breath. The world won't forget Japan that easily.

More astounding, to a lot of us, is the good behaviour of the Japanese, even in the face of total destruction. They still stand in orderly lines for food. There has been no looting, plundering and rioting, as often breaks out in other parts of the world (sometimes even in normal circumstances). This is also because the Japanese are trained from childhood to always value the group above the individual. The good of the group comes before I, myself and me. That is why few people are hoarding, because they know that hoarding implies they are depriving their neighbour of essential supplies. In previous earthquakes, people rushed out into the street, but almost at once they quietly queued up to pay their shop or restaurant bill. Such is their love for doing the right thing. So even in the worst of situations, they still remain human. In contrast, our culture values the individual above the group, in most situations. The individual is greater than the area, the organisation, the city, state or country. Hence, a lot of people feel they are above the law. Multiply this across a lot of levels of society, and you get a happy state of anarchy (masquerading as democracy). In a functioning democracy, you can exercise your rights because you fulfill your duty. In a democrazy people can freely break the signal, or throw garbage on the street, or bribe, because a) they don't care b) they don't feel the street is their country and c) they usually don't feel Indian. The identity of Indianness is usually overshadowed by the identity of the community. It is always 'I am Gujarati, Bengali, Tamil, (fill in any state)' before it is 'I am Indian'. We were a bunch of kingdoms earlier, and we still are a bunch of kingdoms, strongly based on linguistic lines. For the North Indians, everyone south of Mumbai is a 'Madrasi'. For the South Indians, everyone north of Mumbai is a Northie. For the Mumbaikars, Mumbai is its own country. So the general 'Me before all else' attitude has made our country very fertile for corruption. It is rampant at all levels, in all places, barring a few. 2010 may have been the Year of the Tiger in the Chinese calendar, but in the Indian calendar it was the Year of the Scammers. There was 2G, Commonwealth Games, Adarsh Society, Satyam, Ramalinga Raju, Raja and his Batcha, Swiss Bank, and the evergreen politicians being bought with wads of notes that were the size of bricks. And these are just a few of those that made the headlines. One can't imagine the amount of money changing hands under the table across all levels. No system is the system, with money as the new God. Scams are the new democracy, as everyone can freely indulge in them. It's scamming by the people, for the people and of the people. And we are all part of the system. I plead guilty. In 2006, some friends and I bribed a peon at a prominent art college in South Mumbai to get our certificates. The certificates were rightfully ours by the way, and we didn't have to do it, but the peon openly and shamelessly asked three of us students for a bribe. Except that he called it a 'gift'. Filled with disgust, and in shock, we didn't want to give in. We didn't belong to that college, and we also didn't want to make numerous trips there to get it out of him. He would definitely trouble us if we didn't pay him. Our lame excuse is we had no choice. The real reason is that we were cowards who wanted the easy way out. There is no real excuse for bending the rules to suit your own convenience. We put 'me' before the greater good. So the price for 3 pieces of paper (also known as certificates) was Rs 100/- total. Japan is grappling with radiation, but India has to grapple with something more dangerous in the long-term. The debates over nuclear power, safety, environmental destruction and disaster management will rage and die out as issues bulldoze one another. But good sensible behaviour, basic ethics, and the decision to do right, even when nobody is watching, is, well, the strength of the Japanese alone.

0 Comments

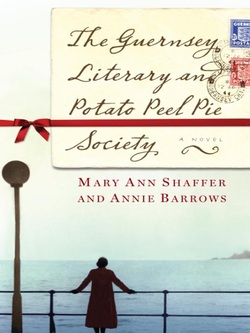

The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society by Mary Ann Shaffer and Annie Barrows, is a long title for a not-very-long book. Set in the time of World War II, on the island of Guernsey, a tiny little island off the coast of England, it tells the story of the islanders, and a visitor.

Due to the war, there was a great shortage of food and basic amenities. The islanders make the best of this situation, by scrimping, sharing and being really creative with the way they use their resources. The situation is worsened by the starving German soldiers who grab whatever food, drink, soap, blankets, etc they can get their hands on. At the height of war-time, this miniscule island is almost forgotten by mainland England, and with no supplies reaching them, things are really hard. Even though the situation looks bleak, the mood is not pessimistic. The islanders are good, strong, simple folk, who help each other, rally around, and keep the group's spirit flying high. One of the ways they do this is by starting a literary society, which meets often (and secretly) to read and talk about their favourite books. They are enthused enough to start writing too. The best part is, the entire book is in the form of letters, much like another wonderful book, Love Letters, by AR Gurney. Through letters traveling between the various characters, one gets personal insights into the nature of people's lives, loves and human nature. The letters gradually unravel the story, bringing forth the characters of people, and the incidents that occur. Though a work of fiction, the authenticity makes it seem like non-ficiton. Most heartening are the little things that give people joy in hard times, and how human contact is so essential to us all. One realises the value of the 'softer' things in life, such as literature in this case, and why we need it as human beings. We take it for granted till it is denied to us. The book is reminiscent of a wonderful quote by Albert Camus, "In the midst of winter I finally learned that there was in me an invincible summer." What's the biggest difference between working by hand (illustration for instance), and working on the computer? It is the absence (or presence) of Ctrl Z. When you draw by hand, you can't undo things easily. The thing drawn remains drawn (dammit!).

The Ctrl Z (or undo option) has changed the way we work and the way we think. Since everything can be undone, sometimes nothing is done very seriously. On the other hand it emboldens us to try new things, however stupid they may seem. Ctrl Z is forgiving. It tells you, you are human, you can do it again, don't sweat it. When you work by hand, you are slower and surer, because you have to be. It is old-school. Working by hand takes the examination first and gives you the education later. If you fail, you start all over. Ctrl Z has taken the edge of drawing. It has given us a plan B. Ctrl Z (Command Z) is a state of mind, which becomes a whole way of working. You can take three leaps forward, because you know that you can always reverse in minutes. Ctrl Z has created a culture of impatience, but also a culture of limitless experimentation. The digital camera has been the Ctrl Z culture of photography. Previously, people used film. It had to be loaded, used, wound, spooled, developed, fixed, and finally printed into a contact sheet. The long process ensured that we carefully composed our shots, and only took a shot if we were pretty sure that was what we wanted. You ended up with photos that were fewer in number, but better in quality. With the digital camera you may shoot hundreds, and still may not turn out with a great one. That's because we shoot without thinking. Ctrl Z has made us (among other things): 1) Fast 2) Exploratory 3) Indecisive Since humankind is at that incredibly exciting stage of leaping from the Gutenberg era to the iPad era, both eras stand to gain the best from each other. And in the process both are evolving almost faster than we are. This review contains spoilers Once in a blue moon you get to see a movie that is so real, moving and brave, you can't forget it for a long time. Das Leben der Anderen (The Lives of Others) is about the suppression of artistic, literary and intellectual expression in East Germany. Any piece of writing, theatre, movie, or art is strongly controlled by the Government of the day, known as the Stazi. Any piece of work not in keeping with their propaganda, is censured and controlled to the point of complete destruction. The Stazi often resort to bugging people's homes with devices, and spying on their every word and act. The only thing that remains private are thoughts, and even they get exposed through double-crossers. An officer of the Stazi is given the job to closely watch a couple. The man is a playwright, and the woman an actress who stars in most of his works. They know what suppression has done to their close friend, a film maker, who did not abide by the rules. Stifled by the lack of any opportunity to work freely, he is completely destroyed. The Stazi dictates how any creative person tells their story, paints their paintings, makes their films, or enacts their performances. This couple still seek to find a way out for their creative voice. The officer who is listening into their every conversation in a dingy attic, begins to be strangely moved by things he hears. From being completely pro-Stazi, he goes over to the other side, in a slow progression. As a continuously falling drop of water ultimately shatters a rock, this officer's rigid beliefs are slowly broken down, one by one, as he listens to their way of life. His whole identity, his very being undergoes a transformation, proving that even in the hardest of people, there is still a human heart. The story has more plots and complexities, and is a deep tale of love, politics and double-crossing. The Stazi officers often search the couple's apartment when they are away. At one point, this officer secretly pockets a book he sees lying about. Later, at home, he opens and reads the book, a simple act that has been discouraged and almost banned by the Stazi. The beauty of the moment, when he discovers that simplest and happiest of joys, of just pure reading, is indescribable. The words on the page give him happiness, after years of being brainwashed that books are bad. There are many more such moments in the film. The playwright meanwhile gets a chance to write a story about the harsh realities of East Germany, and be published in a West German magazine, remaining anonymous all the time. He is provided with a special typewriter to do this task, in utmost secrecy. The typewriter becomes the most dangerous object in the house, for if it is found, it has dire consequences for the couple. It is almost like a deadly piece of evidence, the murder weapon, or the corpse, which the Stazi struggle to find, and no one wants to reveal. Everything revolves around it, at one point. It is a life and death situation, quite lliterally. The writer's tool becomes the most incriminating piece of evidence, for the crime of honest writing. The woman has her own struggle and anguish, as she is used and abused by the powers that be, and remains helpless through it all. She is at the mercy of a man in power. She sells her soul to buy the couple the little creative freedom that they enjoy. How far would one go for one's art? Far becomes too far at times. Tragically, the double life she leads destroys her from within, as it has done to others. Only the playwright gets the chance for meaningful contribution to his work, but he pays heavily for it in other ways. Lives are lost for creative expression, something which is taken for granted many a time. Yet, in an culture of animosity and supression, a hard-headed officer begins to trust again. |

Archives

June 2018

Categories

All

LinksThe New Yorker Old Blogs |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed