|

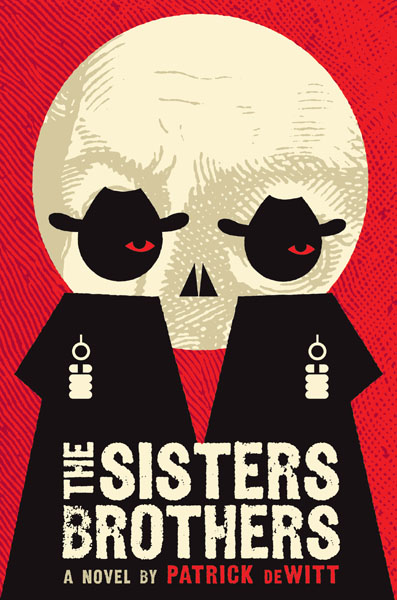

Two brothers, and their travels and travails as they move across America, are well captured by Patrick DeWitt in The Sisters Brothers, a runner-up for this year's Booker Prize (The Booker Prize finally went to Julian Barnes). These two contrasting characters are on their way to loot and kill, but their experiences change them, build them and burn them.

Told in the first person, by the younger (and relatively milder) brother, The Sisters Brothers is captivating right from the start. The writer's descriptive power builds up vivid images of the wild, wild West. One can see the filth, smell the blood, the bullets, the dust, and come face-to-face with the ugly and wretched characters all integral to the plot. DeWitt uses simple language, nothing complex here, and even the thoughts of people are simple, direct and in-your-face. One experiences the hard, tough life, made easy only by regular alcohol consumption and the occasional woman. The brothers are two hardened killers (especially the elder one), moving from desolate town to desolate town. They have no one in the world they can trust but one another. Despite their constant bickering and contrasting natures, or perhaps because of it, they grow closer over time. Even in the most hardened person, there is still a thread of humanity. The main story is made interesting by little diversions and sub-narratives. One of these involves Tub, the old, faithful horse that carries the younger brother. Tub has a severely infected eye, yet he plods on. Ultimately he meets his end. The brother's attachment to Tub, and his unwillingness to really give up on him, is bound to pull on the reader's heartstrings. The author launches into 2 or 3 'dream' descriptions, which masquerade as 'Intermissions'. These seem boring and meaningless, as they don't seem to add anything real to the book. Apart from this, there is little to criticize in The Sisters Brothers. The brothers' bizarre adventures give a real picture of an uncivilized place, uncouth people, the Gold Rush, and the desperate greed that accompanied it. But more that the physical things, it is the subtle description of the intangible that is truly gripping. The love-hate relationship shared by the brothers is apparent in their dialogues, which are by turn both nasty and entertaining. One's love and longing for home, and the desire to leave the bad life and be a better person, is strongly contrasted by the other's complete disdain for a civilized and decent life. Unexpected events however, change both of them, and in the end their natures undergo a transformation. Each becomes more like the other. The cold-blooded murderer becomes subdued. The soft-hearted sentimentalist becomes ruthless and calculating, for one last kill. DeWitt is a master of description, and even with numerous details, he never bores you needlessly. It's not easy to make a reader imagine a place they have never seen, but he pulls it of with ease. His characters are unique and quirky, with twisted minds, but good intentions too. They are, in a word, very human, and fallible. Psychologically, they are extremely interesting. What goes on in the killer's mind? Does he ever regret his life? Does he really think that his killings are justified? Can he ever really escape his past and make a fresh start? How long can a person kill for money? Someone who doesn't squirm while shooting a man clean in the face, has qualms when it comes to killing a horse. Everyone gets attached to something, even if it is an animal. The quick pace, and descriptions that hold nothing back make this book like a Western movie playing across the pages. Sometimes, I even found myself reading in a Western accent. Blood flies, eyes are gouged out, guns are drawn and chemicals gorily eat away gold prospectors, while the two brothers stick together through it all.

0 Comments

|

Archives

June 2018

Categories

All

LinksThe New Yorker Old Blogs |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed