|

About Alphabets – Some Marginal Notes on Type Design by Hermann Zapf

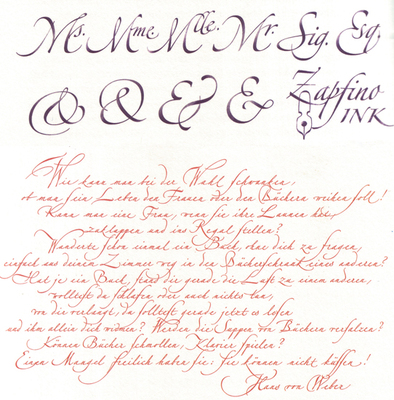

The M.I.T. Press, Cambridge/Mass. And London, England The humble size and unassuming cover of this book reflect the character of the author, Hermann Zapf, in that he is not one to shout about the work he has done, even though his accomplishments in the field of type design and calligraphy are unparalleled. The book is a simple autobiography of one of the greatest graphic and type designers of our time. Written in the first person, the book is an interesting account of his early beginnings, and his development. Being trained in the old school of type design – when letters were drawn by hand and then manually cut out of metal blocks – he provides interesting insights and observations that would rarely occur to modern day typographers and graphic designers. For example, the kind of metal used to engrave out the letters was of prime importance, and it was a relief when lead was introduced, as it lent itself to re-soldering, and new bits and pieces could be fused into the original block of the letter if too much had been cut off. At the same time, several of his concerns hold true even today, such as the basic aspect of readability, and durability of the typeface after thousands of print runs. Hermann Zapf is not concerned with purely the aesthetic aspect of letter forms, (and he is a master of this) but also spends large amounts of time and energy with the functional aspect. Being a calligrapher par excellence reflects in some of his creations, of which there are several examples in the book. The author also briefly touches about his enlistment in World War 2, and the trauma it inflicted. Even during the war, he spent spare time sketching the forms of flora and fauna, as a base for a Flower Alphabet he was to create. After the war, the author starts creating typefaces for specific clients and purposes, and sets up his own Stempel Foundry. Later in the sixties he talks about his experiences in teaching in the USA, and also his involvement with book binding and publishing. As Hermann Zapf himself acknowledges, it is a hard task to write an autobiography about oneself, but he has managed it with aplomb. The book is what its title claims it to be ‘marginal notes on type design’. Although a few more personal experiences included would have encouraged more readership. Nevertheless, one can feel his passion for typefaces and their creation, when he often refers to them as ‘children’ or ‘daughters’, having different parents, and he talks about the process to ‘name’ the ‘child’. And indeed, in that time, creating a typeface was a longer and possibly harder process than having a child, with as much joy at the end. The author reflects on culture, the dwindling time people have for reading (even in those days), and how that affects the role of a type designer. Though schooled in the traditional way of creating type, he projects the new challenges for type designers, as photo-compositing and newer technologies become mainstream. Though deeply inspired by the past, by typographers and letterers of previous centuries, and masterpieces of type such as the Trajan column, he looks keenly to the future, and warns against the ‘romanticizing’ of the past. He also softly, though manifestly shows his dislike for ugly new typefaces sprouting like weeds, especially the craze of sans-serif types. The book is of small size, easy to hold, and set in Linotype Optima, one of his own graceful creations. The line spacing differs, as the closer set text is a commentary on the main text, and is an interesting way of writing an autobiography, rather like two voices of the same person speaking simultaneously. He favours unusual punctuation in place of speech marks, which is quite refreshing. Of all his fonts, my personal favourite is Zapfino, which is a delicious blend of calligraphy and typography. Somehow, he has combined the two, while doing justice to both. The result is beautiful, graceful letter forms, with generous sweeps and swirls. He is also the creator of Palatino. This is a book that anyone interested in type design and typography can read, as it is informative and inspiring. More importantly, it is a first-hand account of the journey and struggle of a type designer, the challenges he faced working with the technology at the time, and the culture prevalent in those years.

1 Comment

It's a strange phenomena, but most people, including a lot of graphic designers think fonts are free as the air we breathe (which, I have no doubt, will cost us one day). But typefaces/fonts are not. A huge amount of effort goes into creating a single typeface. And that is just one basic version of it. More effort goes into creating different weights of the entire family. Yet, fonts are the most plagiarized of all resources, more than even the Internet or Wikipedia. I used some 'illegal' (not purchased) fonts too, as a student. In the Indian context, a lot of people think buying fonts is just a waste of money, not realising the importance of buying fonts for commercial and published work. Some fonts are expensive and may eat away a good chunk of their design budget. People's reactions range from:

Fonts aren't free? What the hell! Why bother, lets just use a pirated version. Why are we thinking of these fonts? Lets just download from dafont.com Can't we use this font and just change it a bit? Ok, lets use only those pre-loaded on the machine, at least that way we can save money and still be legal. Can they sue us? Lets buy some fonts. It's a good investment. Sadly a very slim percentage of the population will say that last line. People need to be informed and educated about the importance and value of fonts. A lot of people ask the second last line. It's only the fear of punishment that makes people want to do the right thing. Why should we buy fonts? 1) They are good investments. When you buy a good workhorse font, from a type foundry, it goes a long way. You get a whole font family, that could be anything from two to forty weights. Just that one font family alone can be used in innumerable ways, in countless projects, over the years. Take into account the fact that most good fonts have been around for decades (Helvetica) or centuries (Caslon, Didot, Bodoni). One solid font family purchased today can probably be used most of your lifetime. 2) It's the right thing to do. There is no other way to explain this. 3) Respect the creator. When you buy fonts, you are respecting, acknowledging and encouraging the designer somewhere, to create more. If everyone stopped buying fonts and used pirated versions, font designers would have to give up their careers. And then we would all be stuck using Helvetica forever. 4) There are fonts, and then there are fonts. Sites like dafont.com have their time and place, I believe. It's passable to use those fonts in student projects, your brother's class poster or a card for your girlfriend. In short, they are mostly (not always) amateur. It's not a great idea to use them on a client brochure, or a magazine, or for any professional/commerical work. Many times these fonts won't be kerned right, or won't have all the necessary glyphs. A lot of fonts on such sites are tweaked, squeezed and squashed versions of real, solid fonts. 5) The great are invisible. The really good fonts work invisibly and silently. They won't be shouting for you to see them. In fact, you may not notice them. They are designed to aid reading, not draw attention to themselves. So if you want people to actually read your text, and not just admire it, these are the fonts to go for. That is why big news agencies or newspapers commission their own fonts which are highly readable. Fonts are carriers and dispensers of content. Have a fontastic week. |

Archives

June 2018

Categories

All

LinksThe New Yorker Old Blogs |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed