|

If Only They Could Talk

It Shouldn’t Happen To A Vet Let Sleeping Vets Lie Vet In Harness Vets Might Fly Vets In A Spin I read the above works by James Herriot for the first time almost twenty years ago, and I’ve reread them countless times since then. It’s hard to find a writer this lovable. As you probably guessed from the titles, James was a veterinary surgeon in the 1930s in Yorkshire, England. His compassion, love and sense of humor are obvious in his writings, both towards his patients as well as their owners. His opening chapter describes his struggle to deliver a calf in the middle of the night, while the farmer has little faith in him, as he is a young, inexperienced vet. The book has countless such anecdotes from angry bulls to delightful kittens and cheeky parrots. One of the most interesting segments is about Tricki Woo, a pampered Pekinese dog belonging to a rich old lady. Equal importance is given to the farmers, their crusty exterior hiding some of the most generous and wonderful people one could meet. And of course there is the love of his life, Helen, but I won’t say more. Early in the book James joins the veterinary practices of Siegfried, one of the most interesting and entertaining characters you can meet in literature. One can only wish such hilarious and understanding bosses existed in real life too. James was certainly lucky to have one. And even more entertaining is Siegfried’s younger brother Tristan, a fun-loving veterinary student who waltzes in and out of the house and the books, adding more hilarity. But it is not all laughs. There are many moments when this writing can bring tears to your eyes, especially when a beloved animal passes away or has to be put down. In the last three books James and Siegfried are enlisted in the Royal Air Force (RAF) to serve in WWI. He weaves those tales in and out of the ones of his old life as a vet with mastery. This is a large volume of writing, but it never gets boring because his insight into human and animal nature is profound. These books are so vivid and enriching, they leave you feeling that you lived in his world. James Herriot takes you right into the lives and hearts of the people he knew, and makes you feel as if you know them too. PS: Sorry for the lousy picture but it's the only one of the edition I own that I could find online.

3 Comments

Author: Tan Twan Eng

Genre: Fiction Keywords: Intriguing. Mysterious. Historical. This is the tale of a judge who has been a prisoner of war in a Japanese internment camp in Word War II. After the war she tries to make sense of her life. She is also battling an illness in private. While visiting old friends, she meets a Japanese artist who was previously the Emperor’s gardener. She is conflicted, as she wants to learn the Japanese art of creating a garden from a master, but she also hates the Japanese for what they did to her and her people. The Japanese philosophy of building a garden, which goes beyond the obvious, affects her without her knowledge. She also overcomes her hatred and anger against the gardener to become friends, and later lovers. This tale moves effortlessly across different times of her life. Her journey draws the reader in. Although the book is set against the backdrop of war, it is not only a war story. We see her young days with her parents and sister in Malaya before it was torn by war. We get to know her as a well-known judge, and later, as a person searching for peace, and searching for herself. The slow revealing of her character, and the story, makes for a wonderful read. Author: Arthur Miller

Genre: Realistic fiction (maybe) Keywords: Moving. Intense. Disconcerting. I don’t read many plays but All My Sons is more than just a play. Based on a true story, it reveals the deeply complex and fundamentally flawed nature of human beings. It delves into ethics and idealism, and questions how personal greed and selfishness allow people to ignore their moral responsibilities. Its broader themes hint at the corruption prevalent in any system, and it questions the American dream of the 1950s. All My Sons is so relevant to India today; it will strike a chord in many readers’ hearts. A story that stays with you, and haunts you for a while. Author: Bel Kaufman

Genre: Epistolary novel Tags: Realistic. Humourous. Unconventional. My cousin – a school teacher – never stops raving about this book. So I finally got my hands on it. And no wonder teachers love it, because no book explains the life of a teacher with all its trials and triumphs as well as this one. Set in a school in the New York area in the 1960s, Up The Down Staircase rings true even today. The book unfolds in different voices, in the form of dialogues between people; notes between teachers, from the trash, or the suggestion box; letters between characters; scribbles on papers and so on. This lends authenticity, landing the reader smack into the life of a teacher, with all its challenges and rewards. It also makes for an interesting read, as you experience school life from various points of view. We see the growing pains and difficult lives of certain students, the insecurities and pettiness of some of the staff, and the dedicated teachers who truly love their profession. There are plenty of little stories sprouting around the main theme. Even fifty years later and continents away, one can relate to and enjoy Up The Down Staircase. Several years (ten or more) ago, I tried to read John Steinbeck. At that time I struggled through The Grapes of Wrath, which is known as his best work. I couldn’t quite digest it. But sometimes, certain books captivate us when we are of a certain age. You have to come to the book at the right moment in your life. I think that happened only now. Steinbeck’s writing is spellbinding, a slow and exquisitely detailed unfolding of life and people in California in the 1920s and later. Steinbeck has been rightly called a ‘giant of American literature’.He writes about the simple everyday lives of people, but it is incredibly realistic, stirring, and thought provoking. His work is a fabulous time machine, a journey back to a very different America, when farms filled Palo Alto, and many struggled against crippling poverty. Some of his descriptions, especially of the hardy farmers and their families, resonate with the sorry state of farmers in India today. Like all great writing, the themes are universal. His characters lived in a different time and place, but they are so real, you feel you know them personally. Closer home, Rohinton Mistry is the writer who reminds one of Steinbeck. The Grapes of Wrath

Touching. Compelling. Philosophical. The book describes the journey of a family of poor farmers — from Oklahoma to California — in search of better land and a way out of poverty. They travel on Route 66, stopping in makeshift camps. They have to struggle for food, water, and gas, all the while running out of precious money. But more hard-hitting is the hope that keeps them going, and at moments it seems to be all that holds them together and keeps them from going insane or turning criminal. There are incredible descriptions of the land and the people who inhabit it. Steinbeck makes you feel the dust in your shoes and the burn in your belly as you walk alongside the Joads. The concluding scene of the book is powerful and unforgettable. The Moon is Down Suspenseful. Dark. Intriguing. This story is set in a small town in Europe during World War II. Although the countries haven’t been named, it is obviously German-occupied territory. When an enemy solider orders a townsman to work in a mine, he retaliates and kills the soldier unintentionally. The soldiers then execute him by a firing squad. This incident turns the townspeople against the soldiers. Though they are largely unarmed, they start plotting revenge. The atmosphere of secrecy and animosity takes a toll on the soldiers' spirits. The town's Mayor is faced with a hard decision, an existential crisis. The book reveals the great truth that there are no truly peaceful people. Under threat, everyone changes, often for the worse. Finally, the book is a great proponent for peace, as it reveals the utter futility of war. East of Eden Rich. Emotional. Biblical. This is truly an epic, following the lives of two families in the Salinas Valley. Their interwoven lives and intricate back-stories make this a captivating tapestry. Most interesting is the female character Cathy, a dark and twisted soul who will stop at nothing to get what she wants. It is not often that one encounters a powerful female villain in literature, and this is one hell of a gal. This is a journey through several people’s lifetimes, both physically and emotionally. Although the ending doesn’t have the same impact as the end of The Grapes of Wrath, it is still a very soul-satisfying read. Cannery Row Humorous. Simplistic. A story set in Monterey — a town in California — and the characters that live on one of its streets. A group of poor friends wants to do something nice for Doc, a person who is always kind to them. They have good intentions, but in their enthusiasm they mess up their plan and have the reverse effect. They cause Doc considerable trouble. A humorous read, definitely lighter than his other works. But at times it becomes a little monotonous. Personally, this is the only book of Steinbeck that I did not absolutely love. Of Mice and Men Poignant. Sorrowful. Two migrant workers are strongly bonded together, and share the dream of owning their own land someday. They work on a ranch. One of the workers has a limited mental capacity but unlimited strength. One day, he kills the ranch-owner’s wife, entirely my mistake and is petrified. He runs away but is followed by a lynch mob. It is upto the other worker to save him from a painful death. This is a heartwarming and heartbreaking tale of friendship, dreams, hope, and the unforgiving side of human nature. Author: Sheena Iyengar

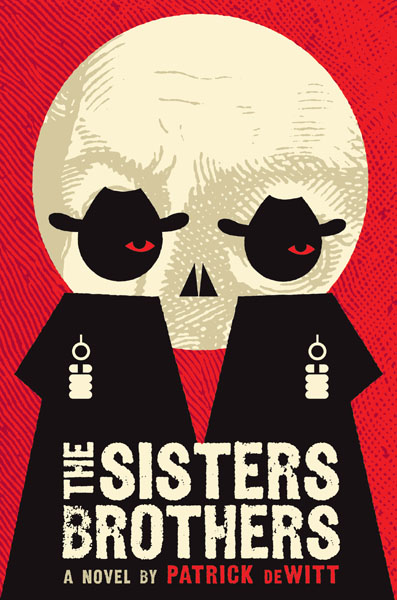

Genre: Non-fiction Tags: Informative. Interesting. Insightful. How do we make the choices? This book analyses factors that influence choice, such as cultural conditioning, our perception of the situation, being in or out of our comfort zone, and so on. The author discusses research and experiments in the field, and breaks some myths such as – more choice is always a good thing. We see how we make choices in both the mundane (which butter to buy), and the emotional realms bl(family-related decisions). Most interesting is the fact that humans – and even animals – feel happier when they believe they are being allowed to exercise choice (even if it is an illusion of control). One can understand why we celebrate or regret certain choices. We can understand if our choices are driven by our personality, our convictions, or our cultural surroundings. Two brothers, and their travels and travails as they move across America, are well captured by Patrick DeWitt in The Sisters Brothers, a runner-up for this year's Booker Prize (The Booker Prize finally went to Julian Barnes). These two contrasting characters are on their way to loot and kill, but their experiences change them, build them and burn them.

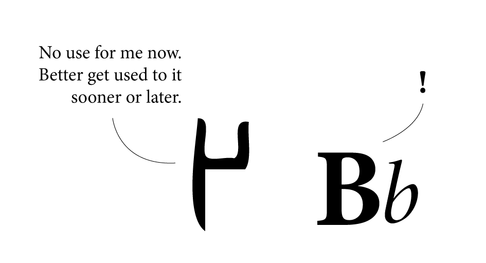

Told in the first person, by the younger (and relatively milder) brother, The Sisters Brothers is captivating right from the start. The writer's descriptive power builds up vivid images of the wild, wild West. One can see the filth, smell the blood, the bullets, the dust, and come face-to-face with the ugly and wretched characters all integral to the plot. DeWitt uses simple language, nothing complex here, and even the thoughts of people are simple, direct and in-your-face. One experiences the hard, tough life, made easy only by regular alcohol consumption and the occasional woman. The brothers are two hardened killers (especially the elder one), moving from desolate town to desolate town. They have no one in the world they can trust but one another. Despite their constant bickering and contrasting natures, or perhaps because of it, they grow closer over time. Even in the most hardened person, there is still a thread of humanity. The main story is made interesting by little diversions and sub-narratives. One of these involves Tub, the old, faithful horse that carries the younger brother. Tub has a severely infected eye, yet he plods on. Ultimately he meets his end. The brother's attachment to Tub, and his unwillingness to really give up on him, is bound to pull on the reader's heartstrings. The author launches into 2 or 3 'dream' descriptions, which masquerade as 'Intermissions'. These seem boring and meaningless, as they don't seem to add anything real to the book. Apart from this, there is little to criticize in The Sisters Brothers. The brothers' bizarre adventures give a real picture of an uncivilized place, uncouth people, the Gold Rush, and the desperate greed that accompanied it. But more that the physical things, it is the subtle description of the intangible that is truly gripping. The love-hate relationship shared by the brothers is apparent in their dialogues, which are by turn both nasty and entertaining. One's love and longing for home, and the desire to leave the bad life and be a better person, is strongly contrasted by the other's complete disdain for a civilized and decent life. Unexpected events however, change both of them, and in the end their natures undergo a transformation. Each becomes more like the other. The cold-blooded murderer becomes subdued. The soft-hearted sentimentalist becomes ruthless and calculating, for one last kill. DeWitt is a master of description, and even with numerous details, he never bores you needlessly. It's not easy to make a reader imagine a place they have never seen, but he pulls it of with ease. His characters are unique and quirky, with twisted minds, but good intentions too. They are, in a word, very human, and fallible. Psychologically, they are extremely interesting. What goes on in the killer's mind? Does he ever regret his life? Does he really think that his killings are justified? Can he ever really escape his past and make a fresh start? How long can a person kill for money? Someone who doesn't squirm while shooting a man clean in the face, has qualms when it comes to killing a horse. Everyone gets attached to something, even if it is an animal. The quick pace, and descriptions that hold nothing back make this book like a Western movie playing across the pages. Sometimes, I even found myself reading in a Western accent. Blood flies, eyes are gouged out, guns are drawn and chemicals gorily eat away gold prospectors, while the two brothers stick together through it all. Just finished proofreading somebody's Diploma (thesis) document. I don't have any right to divulge the topic and the details of it, but part of it was about the development of language, script and how we read letters and words. There is still no really conclusive theory on how language developed. Was it to express emotion, need, signal danger, or for the purpose of trade? Who knows. We don't really know how or why humans started making intelligent sounds and then giving signs to the sounds they made. This was a huge evolutionary leap. Animals too have complex language and communication systems, but human language has developed to an abstract system of signs.

The letter A is just a notion of the sound it represents. The 'A' could well be a square or circle instead of A. At some point in our long and convoluted history somebody decided we needed signs to communicate. And that was the beginning of script. Many scripts developed out of a need to keep accounts for trade purposes. Stringing these signs together in various groups led to the formation of words and sentences. We never really read every letter in a word, we just read the word as a group. Reading is as much about pictures as it is about words, because at the end of the day, words are pictures. When someone asks the spelling of the word, one may actually see the word in their head, and know that if it 'looks' wrong, the spelling is wrong. I know, for instance, the i must come after the e, by the image in my head. If e is before i, my brain recognizes it is visually wrong. It doesn't spell wrongly, it looks wrong. It is easier to know spelling when you visualize it. The images of letters that we know today have developed over thousands of years. We have accepted them as much as we have accepted the noses on our faces. Language (especially one's mother tongue) seems to be hard-wired in us. There is very little effort required in thinking or talking in one's mother tongue. We all learnt language at such a tender age, we usually cannot recollect anything to do with the process. It probably wasn't very hard, or we would have vivid memories of it. Learning a second language however, usually proves harder. Most people remember struggling, or at least making more efforts with Hindi, Marathi, English, French or any other language that they learned a little later. Between the ages of approximately 2 to 6, the 'language window' in little human brains is wide open, more than it will ever be in life again. Between these years, children can effortlessly pick up 3 or 4 languages being spoken around them. No one (or very few) will question why A looks the way it does. Why can it not look like X, or a circle? World over, the speakers of a language have a general, unspoken agreement over the form of letters. Adding or removing a letter from a language is like adding or removing a limb. Generations may pass before people realise the loss of a letter, or even a matra. And by then it may be too late to bring it back. Most people may ask, what's the big deal in the loss of a letter, the language is simply evolving. That may be the case, but the loss is still very real. A letter may not have a tangible value, but it carries a wealth of information, symbology, history, culture and identity with it. Adding a letter is also serious business. First, the need for a new letter needs to be strongly felt by most people. How will people know what a new letter means, unless it is told to them repeatedly? Somehow, words are easily dropped from and added to any working language, but letters, not so easily. The loss of languages is a very real threat to culture and diversity world over. We are illiterate when we look at ancient scripts. The Indus Valley script still has the world flummoxed after thousands of years. Changes in scripts have occurred over millennia, often for very down-to-earth reasons. For instance, Gujarati lost the line on top of the letters that Devnagari has simply because the Gujaratis are predominantly a business and trading community, and the loss of the line enabled them to write faster for maintaining accounts and lists. Similarly, a thousand years from now our alphabet may be completely different. We form the language we speak, but it also forms us. I don't know what it is, but spelling and grammar mistakes seem to be on the rise. It could be the auto-correct in Microsoft Word and Google that's pampering (read spoiling) everyone's language benchmark. It could be just sheer laziness, or too many distractions around us. It could be the falling standards of education. It could be the rise of digital devices. We still don't know the real long-term implications of all this technology around us. If mobile phone waves are killing sparrows, they might be messing with our spelling skills too.

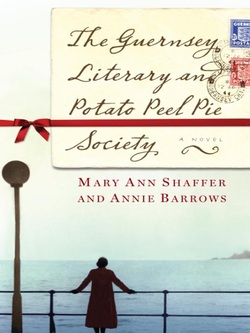

Speaking of mobiles, we can definitely dump some of the blame on the mobile phone and smsing. I love mobile phones and technology. Bt myb thts y we all rite like dis now, evn n collg. Ders no time. I hv frgten de real splings of tings. I also rite in rely shrt sntnces nw. Dis proves we can read ny wrd easly. But we can't use language like that in printed/published work (not yet at least). Language standards, in India can be surprisingly low in places where they should be high. Pick up the Times of India. On any given day, you can usually find one spelling plus one grammar mistake, and you won't even have to read the entire paper to discover them. Errors are especially rampant in the supplementary paper such as Ahmedabad Times. Surprised? Don't be. Recently, someone pointed out a spelling error in a Penguin book. English is definitely not the easiest language to master, with more exceptions than rules. The er and the ar are often confused. "I went to collage." (You couldn't have gone to a work of art). Some errors of course result in pretty hilarious situations. Recently we witnessed the 'Osama/Obama is dead' situation. A slip of one letter can mean something drastically different. Imagine the "Diving Mother that helps one in time of need." (Divine became a water sport). The slips between s and c are countless. Receive and abscess can deceive us all. And you might want to discus something or throw the discuss. Viscous can be vicious to spell. You are pretty likely to find some mistakes in this post, if you read carefully enough. The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society by Mary Ann Shaffer and Annie Barrows, is a long title for a not-very-long book. Set in the time of World War II, on the island of Guernsey, a tiny little island off the coast of England, it tells the story of the islanders, and a visitor.

Due to the war, there was a great shortage of food and basic amenities. The islanders make the best of this situation, by scrimping, sharing and being really creative with the way they use their resources. The situation is worsened by the starving German soldiers who grab whatever food, drink, soap, blankets, etc they can get their hands on. At the height of war-time, this miniscule island is almost forgotten by mainland England, and with no supplies reaching them, things are really hard. Even though the situation looks bleak, the mood is not pessimistic. The islanders are good, strong, simple folk, who help each other, rally around, and keep the group's spirit flying high. One of the ways they do this is by starting a literary society, which meets often (and secretly) to read and talk about their favourite books. They are enthused enough to start writing too. The best part is, the entire book is in the form of letters, much like another wonderful book, Love Letters, by AR Gurney. Through letters traveling between the various characters, one gets personal insights into the nature of people's lives, loves and human nature. The letters gradually unravel the story, bringing forth the characters of people, and the incidents that occur. Though a work of fiction, the authenticity makes it seem like non-ficiton. Most heartening are the little things that give people joy in hard times, and how human contact is so essential to us all. One realises the value of the 'softer' things in life, such as literature in this case, and why we need it as human beings. We take it for granted till it is denied to us. The book is reminiscent of a wonderful quote by Albert Camus, "In the midst of winter I finally learned that there was in me an invincible summer." |

Archives

June 2018

Categories

All

LinksThe New Yorker Old Blogs |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed