|

Several years (ten or more) ago, I tried to read John Steinbeck. At that time I struggled through The Grapes of Wrath, which is known as his best work. I couldn’t quite digest it. But sometimes, certain books captivate us when we are of a certain age. You have to come to the book at the right moment in your life. I think that happened only now. Steinbeck’s writing is spellbinding, a slow and exquisitely detailed unfolding of life and people in California in the 1920s and later. Steinbeck has been rightly called a ‘giant of American literature’.He writes about the simple everyday lives of people, but it is incredibly realistic, stirring, and thought provoking. His work is a fabulous time machine, a journey back to a very different America, when farms filled Palo Alto, and many struggled against crippling poverty. Some of his descriptions, especially of the hardy farmers and their families, resonate with the sorry state of farmers in India today. Like all great writing, the themes are universal. His characters lived in a different time and place, but they are so real, you feel you know them personally. Closer home, Rohinton Mistry is the writer who reminds one of Steinbeck. The Grapes of Wrath

Touching. Compelling. Philosophical. The book describes the journey of a family of poor farmers — from Oklahoma to California — in search of better land and a way out of poverty. They travel on Route 66, stopping in makeshift camps. They have to struggle for food, water, and gas, all the while running out of precious money. But more hard-hitting is the hope that keeps them going, and at moments it seems to be all that holds them together and keeps them from going insane or turning criminal. There are incredible descriptions of the land and the people who inhabit it. Steinbeck makes you feel the dust in your shoes and the burn in your belly as you walk alongside the Joads. The concluding scene of the book is powerful and unforgettable. The Moon is Down Suspenseful. Dark. Intriguing. This story is set in a small town in Europe during World War II. Although the countries haven’t been named, it is obviously German-occupied territory. When an enemy solider orders a townsman to work in a mine, he retaliates and kills the soldier unintentionally. The soldiers then execute him by a firing squad. This incident turns the townspeople against the soldiers. Though they are largely unarmed, they start plotting revenge. The atmosphere of secrecy and animosity takes a toll on the soldiers' spirits. The town's Mayor is faced with a hard decision, an existential crisis. The book reveals the great truth that there are no truly peaceful people. Under threat, everyone changes, often for the worse. Finally, the book is a great proponent for peace, as it reveals the utter futility of war. East of Eden Rich. Emotional. Biblical. This is truly an epic, following the lives of two families in the Salinas Valley. Their interwoven lives and intricate back-stories make this a captivating tapestry. Most interesting is the female character Cathy, a dark and twisted soul who will stop at nothing to get what she wants. It is not often that one encounters a powerful female villain in literature, and this is one hell of a gal. This is a journey through several people’s lifetimes, both physically and emotionally. Although the ending doesn’t have the same impact as the end of The Grapes of Wrath, it is still a very soul-satisfying read. Cannery Row Humorous. Simplistic. A story set in Monterey — a town in California — and the characters that live on one of its streets. A group of poor friends wants to do something nice for Doc, a person who is always kind to them. They have good intentions, but in their enthusiasm they mess up their plan and have the reverse effect. They cause Doc considerable trouble. A humorous read, definitely lighter than his other works. But at times it becomes a little monotonous. Personally, this is the only book of Steinbeck that I did not absolutely love. Of Mice and Men Poignant. Sorrowful. Two migrant workers are strongly bonded together, and share the dream of owning their own land someday. They work on a ranch. One of the workers has a limited mental capacity but unlimited strength. One day, he kills the ranch-owner’s wife, entirely my mistake and is petrified. He runs away but is followed by a lynch mob. It is upto the other worker to save him from a painful death. This is a heartwarming and heartbreaking tale of friendship, dreams, hope, and the unforgiving side of human nature.

0 Comments

Author: Julia Alvarez

Genre: Non-fiction historical novel Tags: Inspiring. Heart-breaking. True. This is a gripping account of the incredibly brave Mirabel sisters who lived under the Trujillo dictatorship in the Dominican Republic. The story is told in the different voices of the sisters, moving seamlessly from first to third person as needed. At times we read of experiences typical to young women anywhere, with light-hearted episodes such as teenage crushes. As they grow up, we read of the non-typical terror of living under a dictatorship, and the personal difficulties they face as women and citizens. The slow rebellion that always boils beneath the surface creates an atmosphere of terrible suspense. Their country’s circumstances made these women into brave, inspiring national heroes. Today I saw The Secret Life Of Walter Mitty. A lovely, moving film, based on a short story by James Thurber. It touches many topics, directly and indirectly. Millions of people spend their lives behind a desk, never striking out on their own, never taking a risk, living lives of soul-crushing anonymity. But that’s not the issue I’m talking about. No ma’am. The movie shows the death the printed version of Life magazine. From Life in paper, it becomes Life dot com. Behind that not-so-smooth transition, many lives (pun unintended) are turned upside down by the heartless, relentless march of technology. It takes many people to make a magazine, or for that matter, any published material. Most people never understand the pain, handwork and joy that go into creating something, especially something that will be printed. Because print has an air of finality. It can’t be coded to make a correction later. There is no option to upload a new file. Written in ink equals written in stone.

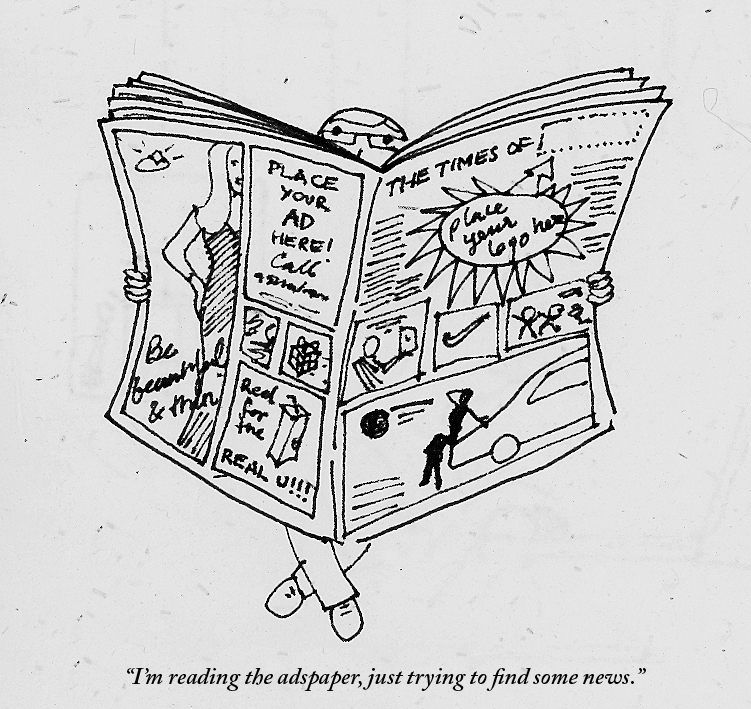

Because of print’s highly demanding nature, there are many different people, each a vital performer, involved in the art of printing and publishing. Did you ever guess that there is someone like Walter Mitty, sitting in his dark room of negatives, sifting through hundreds of little images? He knows them like old friends. There is someone who colour corrects, sharpens and touches up every single image you see in any publication worth its ink. There is someone who composes the pages for print on the offset machine. Each of these people are small cogs in the larger machine. Individuals with expert, specialised knowledge. Unless you work directly with them, there is no access to that amazing tradition and well of knowledge. They never get much credit. The magazine always stands between them and the viewer, like a wall. I’m not bemoaning the rise of digital media, far from it. I love the internet, and all the information, entertainment and cat videos it houses. I’m only wondering if we are losing a entire generation of people, and with them, the knowledge and skill they had, for all time. That knowledge is of no use to us, for sure, but their stories deserve to be told. Walter Mitty tells us one such story. You can see Life online, with more photographs than ever before. But if you hold a Life magazine in your hands, you will see so much more. Behind each image, you can see a quiet person, staring at photographs for hours, checking their quality, so that you gasp wow!, and turn the page. The internet has pampered us sufficiently into believing that content is as free as the air we breathe (even if the latter is polluted as hell). There was a time in the pre-internet days when one had to pay to read. We still pay to read magazines, books, and the newspaper. The newspapers manage to keep it cheap because the advertisers are paying them. We pay just a few rupees because a corporation has paid a few crores to place their advertisement there.

Some sites with good quality content don't wish to sell out completely to advertisers, and they charge for articles. The New York Times does that, as does The New Yorker. While initially it seems putting-off to a reader, in time it makes sense. No one can write for a living for free. And news, or content, like any other commodity or form of entertainment, comes with a price. If you like what you see, you got to pay to have it. And when there is so much not-so-great content out there, the guys who write quality stuff either have to show you ads to survive, or charge you some money. Speaking ads in your face, the Indian press media take it new heights daily. On any given day there are 3 to 4 full page ads in the Times of India. Earlier, we spotted ads in-between the news, and they stood out, because they were few. Nowadays, we spot news items between the ads. So you may have starving Bangadeshis rubbing shoulders with Katrina selling diamonds. Should there be some kind of rule on the amount a paper can advertise? More importantly, is the corporate world deciding what news gets showcased? Don't get me wrong, I have nothing against ads, but I think there can be a better balance. Advertising needs to realize its role in visual culture, and how it affects social values. Our news is stringently edited, while our advertising is not. News and advertising offer us two different kinds of information, and the line between them is blurring. How much news is still objective, is a matter of great debate. How much advertising does not tell us a lie, is a matter of no debate, its very little. The Greatest Movie Ever Sold talks about a related issue, regarding product placement in the film industry. A creatively made, but entertaining and somewhat radical documentary, it's definitely worth a watch. If there can be a city without ads, there is no reason a newspaper can have a few less too. Haven't read any of Aravind Adiga's other books but The White Tiger is a gripping tale of a loyalty, treachery, hatred, love, anger, servants, masters, poverty and wealth. In short, all the extremes of life are covered in it, and in that the author has painted a brilliantly accurate picture of modern India, with a healthy dose of sarcasm and humour thrown in. Told in the first-person, through the eyes of a chauffeur living in Delhi, it's one book that is really hard to put down. After a long time the real tale of 'two Indias' has got the attention it deserves.

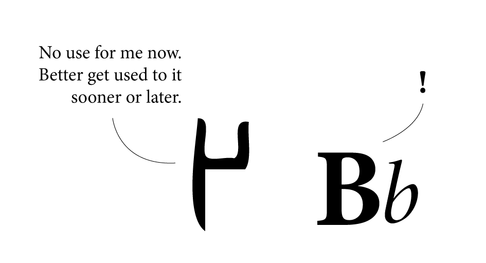

Through one person's story, we get to travel to village India, experience their troubles, then to the typical rich person's world in urban India, the businessman's world and their nexus with politicians, we see the point of the view of the Indian who has just returned from abroad and who believes he can change the country, we deal with his rising frustration. Meanwhile we see the faithful servants, an integral part of the Indian family and Indian way of life. They happily serve their disgusting masters, while deep inside some plot far more evil doings. We see the servant's world, both tragic and fascinating, enriched with servant's gossip, which is, as everyone knows, the best and the juiciest gossip there is. More specifically we get a first-hand account of the driver's world, which revolves around the Honda City, polishing and cleaning the Honda City, the hot memsahib in her miniskirts, the sweet and unsuspecting sahib, the dominating relatives, the other pesky drivers, and the servants hierarchy. We see that older generation of India, who control their children well into adulthood. We see the backwardness that rules much of India, both the super-rich and super-poor. The over-arching theme reflects the reality that India is an anarchy, and lends authenticity to the book. A poor, illiterate village man, through sheer intelligence and cunning, rises to become a millionaire. A rich man's son, full of hope, positivity and with a good heart, still ends up with nothing. Humour, sarcasm and brilliant dialogues make this one fast-paced and insightful read. Once in a while a person wakes up from their situation, and realises what they want in life. If there is nothing holding them back, not even their conscience, then they may achieve the most impossible of things. The human spirit can rise to be anything and fall to be nothing, both in the same moment. Just finished proofreading somebody's Diploma (thesis) document. I don't have any right to divulge the topic and the details of it, but part of it was about the development of language, script and how we read letters and words. There is still no really conclusive theory on how language developed. Was it to express emotion, need, signal danger, or for the purpose of trade? Who knows. We don't really know how or why humans started making intelligent sounds and then giving signs to the sounds they made. This was a huge evolutionary leap. Animals too have complex language and communication systems, but human language has developed to an abstract system of signs.

The letter A is just a notion of the sound it represents. The 'A' could well be a square or circle instead of A. At some point in our long and convoluted history somebody decided we needed signs to communicate. And that was the beginning of script. Many scripts developed out of a need to keep accounts for trade purposes. Stringing these signs together in various groups led to the formation of words and sentences. We never really read every letter in a word, we just read the word as a group. Reading is as much about pictures as it is about words, because at the end of the day, words are pictures. When someone asks the spelling of the word, one may actually see the word in their head, and know that if it 'looks' wrong, the spelling is wrong. I know, for instance, the i must come after the e, by the image in my head. If e is before i, my brain recognizes it is visually wrong. It doesn't spell wrongly, it looks wrong. It is easier to know spelling when you visualize it. The images of letters that we know today have developed over thousands of years. We have accepted them as much as we have accepted the noses on our faces. Language (especially one's mother tongue) seems to be hard-wired in us. There is very little effort required in thinking or talking in one's mother tongue. We all learnt language at such a tender age, we usually cannot recollect anything to do with the process. It probably wasn't very hard, or we would have vivid memories of it. Learning a second language however, usually proves harder. Most people remember struggling, or at least making more efforts with Hindi, Marathi, English, French or any other language that they learned a little later. Between the ages of approximately 2 to 6, the 'language window' in little human brains is wide open, more than it will ever be in life again. Between these years, children can effortlessly pick up 3 or 4 languages being spoken around them. No one (or very few) will question why A looks the way it does. Why can it not look like X, or a circle? World over, the speakers of a language have a general, unspoken agreement over the form of letters. Adding or removing a letter from a language is like adding or removing a limb. Generations may pass before people realise the loss of a letter, or even a matra. And by then it may be too late to bring it back. Most people may ask, what's the big deal in the loss of a letter, the language is simply evolving. That may be the case, but the loss is still very real. A letter may not have a tangible value, but it carries a wealth of information, symbology, history, culture and identity with it. Adding a letter is also serious business. First, the need for a new letter needs to be strongly felt by most people. How will people know what a new letter means, unless it is told to them repeatedly? Somehow, words are easily dropped from and added to any working language, but letters, not so easily. The loss of languages is a very real threat to culture and diversity world over. We are illiterate when we look at ancient scripts. The Indus Valley script still has the world flummoxed after thousands of years. Changes in scripts have occurred over millennia, often for very down-to-earth reasons. For instance, Gujarati lost the line on top of the letters that Devnagari has simply because the Gujaratis are predominantly a business and trading community, and the loss of the line enabled them to write faster for maintaining accounts and lists. Similarly, a thousand years from now our alphabet may be completely different. We form the language we speak, but it also forms us. I don't know what it is, but spelling and grammar mistakes seem to be on the rise. It could be the auto-correct in Microsoft Word and Google that's pampering (read spoiling) everyone's language benchmark. It could be just sheer laziness, or too many distractions around us. It could be the falling standards of education. It could be the rise of digital devices. We still don't know the real long-term implications of all this technology around us. If mobile phone waves are killing sparrows, they might be messing with our spelling skills too.

Speaking of mobiles, we can definitely dump some of the blame on the mobile phone and smsing. I love mobile phones and technology. Bt myb thts y we all rite like dis now, evn n collg. Ders no time. I hv frgten de real splings of tings. I also rite in rely shrt sntnces nw. Dis proves we can read ny wrd easly. But we can't use language like that in printed/published work (not yet at least). Language standards, in India can be surprisingly low in places where they should be high. Pick up the Times of India. On any given day, you can usually find one spelling plus one grammar mistake, and you won't even have to read the entire paper to discover them. Errors are especially rampant in the supplementary paper such as Ahmedabad Times. Surprised? Don't be. Recently, someone pointed out a spelling error in a Penguin book. English is definitely not the easiest language to master, with more exceptions than rules. The er and the ar are often confused. "I went to collage." (You couldn't have gone to a work of art). Some errors of course result in pretty hilarious situations. Recently we witnessed the 'Osama/Obama is dead' situation. A slip of one letter can mean something drastically different. Imagine the "Diving Mother that helps one in time of need." (Divine became a water sport). The slips between s and c are countless. Receive and abscess can deceive us all. And you might want to discus something or throw the discuss. Viscous can be vicious to spell. You are pretty likely to find some mistakes in this post, if you read carefully enough. The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society by Mary Ann Shaffer and Annie Barrows, is a long title for a not-very-long book. Set in the time of World War II, on the island of Guernsey, a tiny little island off the coast of England, it tells the story of the islanders, and a visitor.

Due to the war, there was a great shortage of food and basic amenities. The islanders make the best of this situation, by scrimping, sharing and being really creative with the way they use their resources. The situation is worsened by the starving German soldiers who grab whatever food, drink, soap, blankets, etc they can get their hands on. At the height of war-time, this miniscule island is almost forgotten by mainland England, and with no supplies reaching them, things are really hard. Even though the situation looks bleak, the mood is not pessimistic. The islanders are good, strong, simple folk, who help each other, rally around, and keep the group's spirit flying high. One of the ways they do this is by starting a literary society, which meets often (and secretly) to read and talk about their favourite books. They are enthused enough to start writing too. The best part is, the entire book is in the form of letters, much like another wonderful book, Love Letters, by AR Gurney. Through letters traveling between the various characters, one gets personal insights into the nature of people's lives, loves and human nature. The letters gradually unravel the story, bringing forth the characters of people, and the incidents that occur. Though a work of fiction, the authenticity makes it seem like non-ficiton. Most heartening are the little things that give people joy in hard times, and how human contact is so essential to us all. One realises the value of the 'softer' things in life, such as literature in this case, and why we need it as human beings. We take it for granted till it is denied to us. The book is reminiscent of a wonderful quote by Albert Camus, "In the midst of winter I finally learned that there was in me an invincible summer." This review contains spoilers Once in a blue moon you get to see a movie that is so real, moving and brave, you can't forget it for a long time. Das Leben der Anderen (The Lives of Others) is about the suppression of artistic, literary and intellectual expression in East Germany. Any piece of writing, theatre, movie, or art is strongly controlled by the Government of the day, known as the Stazi. Any piece of work not in keeping with their propaganda, is censured and controlled to the point of complete destruction. The Stazi often resort to bugging people's homes with devices, and spying on their every word and act. The only thing that remains private are thoughts, and even they get exposed through double-crossers. An officer of the Stazi is given the job to closely watch a couple. The man is a playwright, and the woman an actress who stars in most of his works. They know what suppression has done to their close friend, a film maker, who did not abide by the rules. Stifled by the lack of any opportunity to work freely, he is completely destroyed. The Stazi dictates how any creative person tells their story, paints their paintings, makes their films, or enacts their performances. This couple still seek to find a way out for their creative voice. The officer who is listening into their every conversation in a dingy attic, begins to be strangely moved by things he hears. From being completely pro-Stazi, he goes over to the other side, in a slow progression. As a continuously falling drop of water ultimately shatters a rock, this officer's rigid beliefs are slowly broken down, one by one, as he listens to their way of life. His whole identity, his very being undergoes a transformation, proving that even in the hardest of people, there is still a human heart. The story has more plots and complexities, and is a deep tale of love, politics and double-crossing. The Stazi officers often search the couple's apartment when they are away. At one point, this officer secretly pockets a book he sees lying about. Later, at home, he opens and reads the book, a simple act that has been discouraged and almost banned by the Stazi. The beauty of the moment, when he discovers that simplest and happiest of joys, of just pure reading, is indescribable. The words on the page give him happiness, after years of being brainwashed that books are bad. There are many more such moments in the film. The playwright meanwhile gets a chance to write a story about the harsh realities of East Germany, and be published in a West German magazine, remaining anonymous all the time. He is provided with a special typewriter to do this task, in utmost secrecy. The typewriter becomes the most dangerous object in the house, for if it is found, it has dire consequences for the couple. It is almost like a deadly piece of evidence, the murder weapon, or the corpse, which the Stazi struggle to find, and no one wants to reveal. Everything revolves around it, at one point. It is a life and death situation, quite lliterally. The writer's tool becomes the most incriminating piece of evidence, for the crime of honest writing. The woman has her own struggle and anguish, as she is used and abused by the powers that be, and remains helpless through it all. She is at the mercy of a man in power. She sells her soul to buy the couple the little creative freedom that they enjoy. How far would one go for one's art? Far becomes too far at times. Tragically, the double life she leads destroys her from within, as it has done to others. Only the playwright gets the chance for meaningful contribution to his work, but he pays heavily for it in other ways. Lives are lost for creative expression, something which is taken for granted many a time. Yet, in an culture of animosity and supression, a hard-headed officer begins to trust again. Half of a Yellow Sun is gripping and award-winning book by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. It is about the civil war in Nigeria and the struggle to create a new country, Biafra, back in the sixties. It is told through the eyes of Ugwu, a loveable, young houseboy, who comes to work in the house of a revolutionary African professor, Odenigbo. Ugwu is from the village, and everything is strange and fasinating to him. His master is a kind man, who treats him as an equal. Later, the love of Odenigbo's life, Olanna, daughter of a rich Government servant, moves in with them. The book explores human relationships deeply, the relationships and dynamics between man and woman, servant and master, woman and child, man and mistress, people and their government, people and the rich, people and their oppressors, rulers and the ruled, blacks and whites. Local identity overrules the national identity, and also overules common sense and humanity, especially at times of war. War is the great leveller, making refugees out of an entire nation.

Ugwu, Odenigbo and Olanna struggle with the life that has been thrust upon them. Things get worse before they get better, and they undergo trying circumstances, with remarkable strength. This is especially true for Olanna, who grew up in luxury, never wanting anything, but adjusts to life without the basic necessities. They forgive each other, even when grievously wronged, and their very unique bond is the only thing that gets them through extremely hard times. As you read, you feel their pain, and find yourself praying that they get through this alive. The author makes the reader experience the war raging outside, by narrating the war within each of them, and between them. In pain, people do strange things and hurt one another, and these are no exception. They come very close to losing all hope and sanity, but they are pulled back when they are at the brink, by a return to normalcy. Though a novel, it is based on real events, and very real emotions. A great author understands that you can't make people experience an actual event, you can only make them experience the emotions that make the event so real. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie is one such author. Through their dialogues, the book raises larger questions which plague countries that underwent colonial rule. The Nigerian struggle to be their own people, to stop bowing to all Western thought, the enforcing of a national identity, the love of one's country are all issues that any thinking Indian grapples with on a daily basis, even unconsciously. Worse than the economic and political oppression that a colonial power creates, is the loss of identity, the loss of the sense of self, and the hatred of one's fellow citizens, that are the real left-overs of colonial rule. These take generations to remedy. Odenigbo's hope and burning idealism to see a truly independent Nigeria, free of the colonial shadow, almost kills him internally, while the war kills everything externally. |

Archives

June 2018

Categories

All

LinksThe New Yorker Old Blogs |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed